In March, 1818, Mary Shelley's novel, Frankenstein, was published. Eight months later, in Glasgow, an incident occurred in which, it seemed, life was imitating art ...

On the 1st of September, 1818, Matthew Clydesdale, a weaver from the Airdrie area, was brought into Glasgow under arrest, charged with murdering a 70 year old man in a drunken rage. On the 3rd of October, Clydesdale was brought to trial, found guilty, and sentenced to be hung and anatomised - that is, after execution his body was to be handed over to the anatomists for their use.

As this would be the first execution for murder in 10 years in Glasgow, it was, of course, a major public spectacle - hundreds, perhaps thousands of people crowded Jail Square at the foot of Saltmarket on the afternoon of the 4th of November to witness the execution. The gallows had been set up in front of the new High Court building, opened in 1814, and the elegant timber footbridge across the Clyde was guarded by soldiers to prevent the crowd from overloading it in their efforts to gain a better vantage.

Clydesdale was brought out, along with a young man, Simon Ross, who was also to be hung, for an unrelated crime of theft ... the execution was carried out, and it was reported that while Ross twitched for a long time before succumbing, Clydesdale seemed to die with almost no outward signs.

When they were both pronounced dead, Clydesdale was let down and placed in a cart, in which he was transported with all speed up the Saltmarket, across Trongate and up the High Street to Glasgow University (at that time situated where the remains of the British Rail Goods yard now are). (Ross was buried on the following day, in the common ground of the Ramshorn and Blackfriars graveyards, in the grounds of the University).

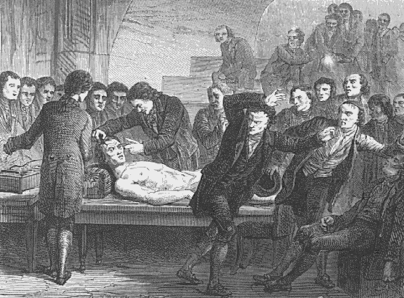

The Anatomy theatre was crowded, not unsurprisingly, for here was another spectacle: anatomists performing their dark operations on a corpse, in full view of the public. The anatomists were Dr. Andrew Ure, senior lecturer at the recently founded Anderson's Institution in John Street (where the Italian Centre is now, as it happens!), and Professor James Jeffray, Professor of Anatomy, Botany and Midwifery (!) at Glasgow University.

This, however, was not to be a typical grisly chop-em-up affair, for one of the major scientific interests at the time was ‘galvanisation’: the animation of dead bodies by means of electric currents. (It was experiments in this area, such as the one in 1803 in London, on human subjects, which partly inspired Mary Shelley's novel, Frankenstein, published March 1818).

Five minutes before the corpse arrived in the Anatomy theatre, Dr. Ure charged his galvanic battery with dilute nitric and sulphuric acids.

A series of experiments were then performed on the corpse, with outwardly dramatic results, as will be discussed later. That should have been the end of the matter. Dr. Ure wrote up an account of the experiments, and indeed delivered a lecture on the topic; only one of the three Glasgow newspapers of the day bothered to write up this coda to the execution. But almost fifty years later, in 1865, this scientific footnote was transformed into a blood-chilling Frankenstein tale by one Peter Mackenzie, a writer and ‘character’ of Glasgow, who claimed to have been present, and to have seen Clydesdale actually brought back to life, to the consternation of the audience, whereupon one of the anatomists snatched a scalpel, slit his throat, and the animated corpse dropped down dead-again. A colourful yarn, and every so often someone rediscovers it and starts to check it out (and the patient archivists at Glasgow University groan inwardly and explain the real story for the hundredth time!).

Jump forward now, to the 1980s, and the arrival in Glasgow of one Dr. Fred Pattison, also an anatomist, and descendent of Granville Sharp Pattison, who was also an anatomist (and graverobber) living and working in Glasgow in 1818. Fred was in Glasgow researching the history of his forebear for a biography; he stumbled across the story, was intrigued, and followed it up. Fred Pattison's account of the 1818 experiments is a revelation (with an ironic sting in the tale!), and we now quote extensively from it (his major source is Ure's own account):

Both Jeffray and Ure were quite deliberately intent on the restoration of life. (Ure commented: “This event, however little desirable with a murderer, and perhaps contrary to the law, would yet have been pardonable in one instance, as it would have been highly honourable and useful to science.”)

Appropriate dissections exposed the various sites selected for electrical stimulation. No bleeding occurred, proving that Clydesdale was dead. Application of the connecting rods to the heel and the spinal cord at the level of the atlas caused such violent extension of the bent knee “as nearly to overturn one of the assistants”.

Next, in an attempt to restore breathing, the rods were connected to the left phrenic nerve and the diaphragm, “The success of it was truly wonderful. Full, nay, laborious breathing instantly commenced. The chest heaved and fell; the belly was protruded and again collapsed, with the retiring and collapsing diaphragm”. The process continued so long as intermittent electrical stimulation was applied.

Perhaps the most dramatic events occurred when the current was applied to the supraorbital nerve and heel. By varying the voltage, “most horrible grimaces were exhibited .... Rage, horror, despair, anguish and ghastly smiles united their hideous expression in the murderer's face, surpassing far the wildest representations of a Fuseli or a Kean. -- At this period several spectators were forced to leave the apartment from terror or sickness, and one gentleman fainted.”

Pattison concludes his review of Ure's account by saying that: “At no point did Ure claim to have resuscitated Clydesdale.”

But before doing so, he picks up on an apparently inconsequential note by Ure, concerning an experiment he had been keen to try, but had been unable to for lack of time ... and here comes the sting!: Although Ure concluded in his discussion that direct stimulation of the phrenic nerve was the most promising procedure for restoring life to a dead individual, he did suggest in a prophetic aside that two moistened, brass knobs, connected to the battery and firmly placed on the skin over the phrenic nerve and the diaphragm, might also be effective. Unwittingly, he had come close to describing the electric defibrillator, which, a century later, has saved so many lives. ... gasp!

Footnotes:

During September, 1818, Clydesdale languished in prison awaiting trial. On the 1st and 2nd of September, the first gas lighting in Glasgow was installed in the premises of James Hamilton, grocer, 128 Trongate. On the 18th of September, visitors to the Theatre Royal in Queen Street experienced a performance of Mozart's Giovanni and Figaro in the first theatre in Britain to be illuminated with gas!.

In 1812, the entrepreneur Henry Bell launched the “Comet”, the first commercial steamship service in the world, plying between the Broomielaw and Helensburgh. On Friday 9th October, 1818, with Clydesdale now convicted and held in the condemned cell, a visitor to Glasgow (from County Mayo, it is thought), well taken by the city of Glasgow, wrote that he had counted 16 steamboats in the Broomielaw!

At the very time when Dr. Andrew Ure was attempting to resuscitate Matthew Clydesdale, he was in the middle of a domestic situation that would lead, the following year, to a successful divorce trial, on the grounds that his wife had had a child by ... Granville Sharpe Pattison!

Pattison is a fascinating character, and Fred Pattison's biography tells his story well: he was tried in 1813 on a charge of grave robbing (from the Ramshorn graveyard!) for illegal anatomical research (he had anatomy rooms in College Street, a couple of hundred yards from the Ramshorn). The verdict, principally due to some macabrely comical confusions with regard to the dissected body of the unfortunate grave robber, was: “not proven” - or, as popularly translated: innocent, but don't do it again! After the Ure divorce scandal he left Glasgow forever, going briefly to London and then to America, where he played a significant role in the development of medical and surgical practice. His father was a Glasgow merchant, John Pattison, who on his death was buried beside his wife in the Ramshorn graveyard; they were subsequently moved to a grander family site in the Glasgow Necropolis, where Granville's remains also lie, brought back from America on his death.

I do not know how Matthew Clydesdale's body was finally disposed of. The practice at that time was to bury executed murderers under the open courtyard in the middle of the High Court building itself, but I have not thus far determined whether this is where Clydesdale was finally laid to rest. Clydesdale left a widow and two young children, the younger born on the 7th of August 1818 - 3 weeks before the assault - and finally christened on the 20th of December 1818, a month and a half after his father's execution.

Time: 1808

Video:

See also:

References:

[1] Dr. F. L. M. Pattison: “The Clydesdale Experiments:an early attempt at resuscitation”, Scottish Medical Journal 31, 050-052 (1986s)

[2] Andrew Ure: “An account of some experiments made on the body of a criminal immediately after execution, with physiological and practical observations”, Journal of Science and the Arts 6, 283-294 (1819)

[3] Peter Mackenzie: “The case of Matthew Clydesdale the murderer - extra-ordinary scene in the College of Glasgow”, Old Reminiscences of Glasgow and the West of Scotland, Vol.2, 490-500 (1865), Glasgow

[4] Louis Figuier, Les merveilles

de la Science (Paris, 1867), p. 653

“Le docteur Ure galvanisant le corps de l'assassin Clydsdale.”

“Dr. Ure galvanizing the body of the murderer Clydsdale.” [4]

Attempting Galvanic Reanimation of the Dead

A nineteenth-century engraving of attempted galvanism